Zandra L. Jordan, Stanford University

Abstract

This article describes a womanist approach to antiracist, racially just writing center administration from the perspective of a Black cisgender director of a writing and speaking center at a PWI. Drawing on womanist ethics and scholarship on race and writing program administration, the author explains the ethical commitments informing the curation of tutors, tutor training, and a cultural rhetorics art display. This womanist work occurs in the midst of intersecting traumas—rising hate crimes against people of color, ongoing anti-black police violence, longstanding systemic racism, and a global pandemic disproportionately impacting Blacks. In response, the author presents the article as a reflective three-part lament and closes with an invitation for solidarity.

Keywords: womanist, antiracism, racial justice, cultural rhetorics, writing center administration, lament

Womanist Curate, Cultural Rhetorics Curation, and Racial Justice in Writing Center Administration

This is a reflective lament in three movements. A guttural, hope-filled wail from an ancestral place—written from the vantage point of a womanist curate. Womanist, a term coined by Alice Walker (1983), is a four-part poetic articulation of a revolutionary paradigm centering the flourishing of Black women in defiance of white hegemonic norms at work in every aspect of society. Walker’s definition expresses an unapologetic appreciation for Black women’s “womanish” ways (p. xi), which Black women scholars, particularly womanist theologians and scholars of religion, have adopted “as a critical methodological framework for challenging inherited traditions for their collusion with androcentric patriarchy as well as a catalyst in overcoming oppressive situations through revolutionary acts of rebellion” (Cannon, 1997, p. 23). This two-fold mission promotes antiracism and racial justice, gleaning from “Black women’s hope and courage in resisting race-, gender-, and class-based oppression” (Marshall Turman, 2019) the “radical subjectivity, traditional communalism, redemptive self-love, and critical engagement” (Floyd-Thomas, 2006b p. 6) needed to root out oppression in all of its forms and to create the just conditions for flourishing.

I take up this womanist work in my professional context as a Black cisgender director of a writing and speaking center at a PWI who is also a curate—an ordained clergywoman engaged in pastoral ministry. The ethic that drives my labor in and out of the workplace, in and out of the church universal, is one in the same. It is centered on liberatory praxis for all, grounded in the lived experiences of Black women with interlocking oppressions. In this spirit, I curate—select tutors and select and arrange a tutor training curriculum that aims to inculcate racial literacy and to promote racial justice in the dialogic, reciprocal interplay between tutors and tutees. This work occurs alongside the Center’s curated exhibition of student artwork depicting diasporic representations of race and identity.

By delineating how my womanist commitments inform my antiracist praxis, I am responding to several calls. Lockett’s (2019) discussion of writing centers as “academic ghettos” with “racialized” practices, exhorts writing center professionals to examine and name their “inclusion politics” and to create antiracist writing center practices that better reflect inclusivity (p. 29). She also advocates for research about Black women tutors, directors, and WPAs that disrupts familiar narratives casting people of color as “students rather than instructors, clients rather than tutors or directors” (p. 28). García de Müeller’s and Ruiz’s (2017) survey research on race and university writing programs calls for scholarship directly addressing how race operates in writing program administration to begin redressing the silence and silencing that maintain systemic racism. Diab et al.’s (2013) framework for “actionable” “commitment[s] to racial justice” encourages writing practitioners to “move from confessional narratives” to doing the work within themselves, with others, and within institutions that can lead to change (p. 20). I offer this lament as a step forward in these directions.

Movement 1: Weeping

We weep. But we are still, even in our most anguished seasons, not reducible to the fact of our grief.

—Imani Perry (2020), “Racism is Terrible. Blackness is Not.”

This is what the Lord says:

“A voice is heard in Ramah,

mourning and great weeping,

Rachel weeping for her children

and refusing to be comforted,

because they are no more.”

—Jeremiah 31:15 (NIV)

On the last day of the spring 2020 tutor training seminar, I cried. Tears had been welling up for days, hovering just beneath the surface as I tried with great emotional difficulty to direct, teach, tutor, and Zoom through a global pandemic disproportionately impacting Blacks and a new spate of horrific murders perpetrated by state-sanctioned police violence. Just one more day of class, I thought, and I would have space to properly lament and process the trauma of this unprecedented yet not entirely unfamiliar time. But concern for my parents who represent the demographic hardest hit by COVID-19 as well as the inability to visit them, because I might be an asymptomatic carrier or could contract the virus in transit, was weighing heavily on me.

At the same time, I was struggling with the image of officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on George Floyd’s neck, squeezing the life out of the father of five as he cried out for breath and for his deceased mother. I was worried about my own brothers whose black skin puts them at risk for deadly encounters with the police. I was having flashbacks of Eric Garner’s unanswered pleas, “I can’t breathe,” as he was being choked to death by officer Daniel Pantaleo. The devastation of emergency medical technician Breonna Taylor being murdered in her own home as plainclothes officers executed a no-knock warrant under cover of night, unleashing a hail of bullets, eight of them striking and killing her, assaulted my mind. The horrific hunting and slaughter of Ahmaud Arbery, a Black man jogging in a predominantly white neighborhood, by father and son Gregory and Travis McMichael, evoked heartbreaking memories of Trayvon Martin’s murder at the hands of George Zimmerman. I’ve never gotten over activist Sandra Bland and the suspicious circumstances surrounding her death in police custody or Renisha McBride’s tragic murder when she knocked on Theodore Wafer’s door, seeking help after a car accident, and he shot her in the face. And recent video recordings of Atlanta college students Taniyah Pilgrim and Messiah Young being violently attacked and tased by police officers left me painfully raw.

It all was just too much to bear. I was by all accounts emotionally drained, physically fatigued, and soul weary when I read students’ tutoring philosophies the morning of our last class. Their words,[1] coupled with the toll of prolonged trauma, removed the last shred of my resolve to restrain my lament until it could be expressed with abandon and without interruption. Tears began to fall as I read:

In the midst of mounting trauma, here was evidence that my efforts were having an impact, and that realization evoked my tears. At the beginning of the quarter, the tutors-in-training largely described effective tutoring as procedural and affective, a matter of asking the right questions and maintaining a positive or encouraging demeanor while working collaboratively with writers. The above excerpts from the final assignment of the training course illustrate more expansive ideologies about the politics of writing center work. The tutors express a commitment to antiracist praxis that appreciates linguistic diversity and actively promotes antiracism (tutor 1); partners with writers to question what counts as academic writing and contributes to the “uplift” of the campus community (tutor 2); does the more difficult work of engaging in conversations about race, language, and identity in the tutorial, “honoring” writers’ “identities” and acknowledging the political effects of rhetorical choices (tutor 3); and affirms the inherent communicability of all language varieties as well as supports writers in challenging the “boundaries of university writing” (tutor 4).

While not all of the tutoring philosophies were as pointed in their articulations of an antiracist, liberatory ethic, and these are varied in their attention to the inter/intrapersonal work involved, as a group the cohort of aspiring tutors engaged in the seminar with an openness and compassion that makes me hopeful about what we can accomplish together. Cultivating a Center culture that is not only antiracist but also life-giving, that does not in the process of “helping” annihilate, devalue, or misconstrue writers’ rhetorical traditions (Camarillo, 2019; Grimm, 2011; Bawarshi and Pelkowski, 1999) but rather supports bolder appreciation for and expression of their own discourses, even as they navigate university demands, hinges on tutoring ethics and praxis. The dialectic between tutors and writers is never neutral, always informed by epistemologies operating, often subconsciously, in the ways that interlocutors engage around language. I want tutors to see themselves as participating in a larger democratic project—co-creating with communicators a campus culture, and in turn a world, that has “plenty good room” for everyone. Given the national political climate and racial tensions in our institutional context, this work is all the more pressing.

Since the 2016 U.S. presidential election, hate crimes at colleges and universities have been on the rise. On average, in the four years prior to the election, 970 hate crimes at colleges were reported. Since the election, that number has jumped to 1250 (Bauman, 2018). The Anti-Defamation League has also reported hundreds of campus incidents promoting white supremacy the days preceding and following the 2016 election and a “258% increase in white-supremacist propaganda from fall 2016 to 2017” that impacted 216 colleges across the country (Kerr, 2018).

On my own campus, #BuildtheWall flyers (Bowen, 2018), a “Racism Lives Here Too” banner prompted by “anti-immigrant hate mail” (Pfeiffer, 2019), a noose hanging on a tree near a residence hall (Shalby, 2019), and most recently controversy over using the N-word in class (Starkman, 2020) evince the continuing and urgent need for antiracist and racial justice work.

Movement 2: Resisting

There are two things I’ve got a right to, and these are, Death or Liberty—one or the other I mean to have.

—Harriet Tubman, from Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman (2015)

Why stay here until we die?

—2 Kings 7:3 (NIV)

My approach to antiracist, racially just work in writing center administration is grounded in womanist ethics, which challenges the denigration of Black women’s epistemologies and advocates for the eradication of all oppression (Cannon, 1985, 1988; Riggs, 2011). While this is the first article in writing center studies to employ womanist ethics specifically, scholars have adopted womanist thought in a variety of fields. Phillips’ (2006) The Womanist Reader features contributors from twelve disciplines, including literature and literary criticism, communication and media studies, education, and religion. Most recently, Lemons’ (2019) Building Womanist Coalitions: Writing and Teaching in the Spirit of Love gathers an array of scholarly voices reflecting on the ways that “women of color feminisms” have shaped understandings of their educational, pedagogical, and professional experiences. McCrary’s articles in JBC and CCC assert the advantages of using womanist sermons in the writing classroom to teach rhetorical analysis (2001b) and to help “other-literate students” leverage their “linguistic capabilities” (2001a, p. 53). Lockett (2018) locates her embodied experience as a graduate writing tutor within a Black feminist/womanist paradigm, noting Black feminist theorists and literary scholars whose work interrogates Black women’s oppressions from this positionality. She also references Walker’s metaphorical distinction of womanism as a richer shade of purple than feminism (Walker, 1983, p. i; Locket, 2018, p. 34). Following Walker’s delineation, womanist theologians and religion scholars acknowledge several waves of womanist thought but infrequently interchange the terms Black feminism and womanism.

My own work foregrounds womanist ethics as a moral standpoint and methodology for engaging the self and others that makes visible the assumptions and taken-for-granted norms undergirding theological writing instruction (Jordan, 2019). Here I illustrate how womanist ethics informs my administration of a writing and speaking center at a PWI, focusing on writing tutor selection and training as resistance work.

Womanist ethicist Stacey Floyd-Thomas (2006a, 2006b) distilled four primary tenets of womanism that other Black women have applied in their scholarship (e.g.; Johnson, 2017; Jordan, 2019):

- radical subjectivity: means by which Black females develop a mature self-awareness and “conscientization” enabling them to resist oppression and participate in their own liberation (Floyd-Thomas, 2006a, p. 16)

- traditional communalism: ways of being in community that “liberate” the whole, revealing through the “re-member[ing]” of Black culture the “traditionally capable” and “universalist” nature of the Black community (Floyd-Thomas, 2006a, p. 78; 2006b, p. 9)

- redemptive self-love: a radical re-visioning of “Black women’s bodies, ways, and loves” that rejects “dehumanizing stereotypes” and reclaims through unconditional self-acceptance their “truer” personhood (2006b, pp. 9-10)

- critical engagement: an obligation, uncompromised in its commitment, to seek the greatest degree of “freedom, justice, and equality,” as informed by Black women’s experiences with interlocking oppressions (2006a, p. 208; 2006b, pp. 10-11)

This ethic is valuable for antiracist writing center administration, because it provides a critical moral and methodological framework for understanding my role as a director committed to racial justice. Radical subjectivity reminds me that I have the authority and responsibility not only to interrogate racist practices but to subvert them. Traditional communalism inspires me to counter narratives of Black inferiority and deficiency with truths about the wit and communicability of Black rhetorical traditions. Redemptive self-love provides an ethic for supporting all marginalized writers in recognizing the value of their linguistic heritage in contradistinction to language bias and discrimination. Finally, critical engagement emboldens me to implement new approaches that promote a radically inclusive, racially just center culture.

One of the primary spaces for this liberatory work in the writing center is tutor training, which begins with tutor selection. I inherited a center and a tutor training curriculum with already established norms for selecting and training writing tutors. Competent academic writers who were passionate about communication and enjoyed working with others were chosen as writing tutors and then introduced to writing center theory and practice, including collaboration as a core value (Lunsford, 1991; Grimm, 2009), scaffolded tutor talk (Mackiewicz and Thompson, 2014) as a tool for mediating directive and nondirective tutoring (Corbett, 2009; Brooks, 1991), discourse communities as an epistemic domain for tutoring writers across disciplines and genres (Swales, 1990; Savini, 2011), and contextually informed strategies for supporting multilingual learners (Myers, 2003).

While the curriculum already in place aligned with many aspects of my own writing tutoring philosophy, it lacked critical engagement with race and ways that writing centers can unwittingly perpetuate white hegemony. I have been working to enhance the hiring and training of a tutoring staff that both reflects the diversity[2] of the student body and embodies critical capacities, like racial literacy and the ability to learn from and with writers, to join them in the process of courageous meaning-making and to do so with a radical appreciation for the wealth of literacies that a diverse community brings.

Recruiting a diverse tutoring staff is challenging, because we must work against commonplace narratives positioning students of color and others from marginalized groups as linguistically inferior and therefore unqualified to tutor. Those narratives drive normative expectations that tutors will be white, middle to upper-class, and native English speakers, while students of color will be among those most in need of tutoring. Our tutor recruitment efforts, therefore, may need to include a cultural shift. In addition to the standard calls for tutor applications and requests for tutor nominations from instructors, direct appeals during in-class writing workshops and new student orientations can play an important role in rewriting the narrative about writing centers, the work we do, and who can do this work. I tell students what we are building at the Hume Center for Writing and Speaking and ask for their help in cultivating a tutoring staff that is representative of the student body and that values the literacies of those marginalized by racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, ableism, and other social ills.

Application materials (e.g. resume, transcript, writing sample, statements of interest, etc.) may not provide insight into a prospective tutor’s capacity for racial literacy and courageous meaning-making, but the interview can be a space of discernment. As candidates speak to their desire to become a tutor, to the mission of a university writing center, to their experiences collaborating with others, to the ways that they might handle tutoring writers across the disciplines, and to anticipated challenges in tutoring writing and the methods they would use to overcome them, I listen with a womanist ear. I take note of their courage, or the potential for acquiring it, to destabilize the hierarchical tutor/tutee relationship for one that is more reciprocal. Through the reciprocity of sharing, receiving, and responding, writers and their tutors can construct ways of seeing, knowing, and communicating that prepare them to engage justly a linguistically and culturally diverse world. I listen for indications that candidates might be up for this kind of collaborative risk-taking, that they possess the humility to learn from and with others and the temerity to question normativity.

Those selected as writing tutors enroll in a required tutor training seminar that explicitly engages race and other marginalized identities. Attention to race and other matters of difference and inclusion are not add-ons to the training curriculum but rather foundational to understanding what it means to be a Hume Center writing tutor. On the first day of the nine-week seminar, I read this statement from the course syllabus to the class and discuss its implications for our work together:

As a Hume writing tutor, you will join a vibrant community of writers and speakers engaged in courageous meaning-making, a reciprocal exchange of ideas in which we (the writer/speaker and tutor) allow others to see who we are—what we think and value, how we reason and communicate—and then open ourselves up to critique and the possibility of change. In the one-to-one tutorial, this work requires an ongoing commitment to learning about writing and writing instruction, honoring linguistic and cultural diversity, and engaging in self-reflection. Seminar readings, assignments, and activities are designed to help you cultivate these practices and develop the foundational knowledge for working with writers across disciplines, identities, and cultures.

The above statement sets the stage for a quarter-long interactive dialogue about liberatory writing tutoring practices and the journey that we will undertake as a community of practice. Through class discussions, written reflections, and other activities, we wrestle with the politics of tutoring, our own positionalities, the university as a place of acculturation, and the possibilities of participating in a larger democratic project—constructing through one-on-one, dialogic interactions with writers, the discursive worlds in which we want to live.

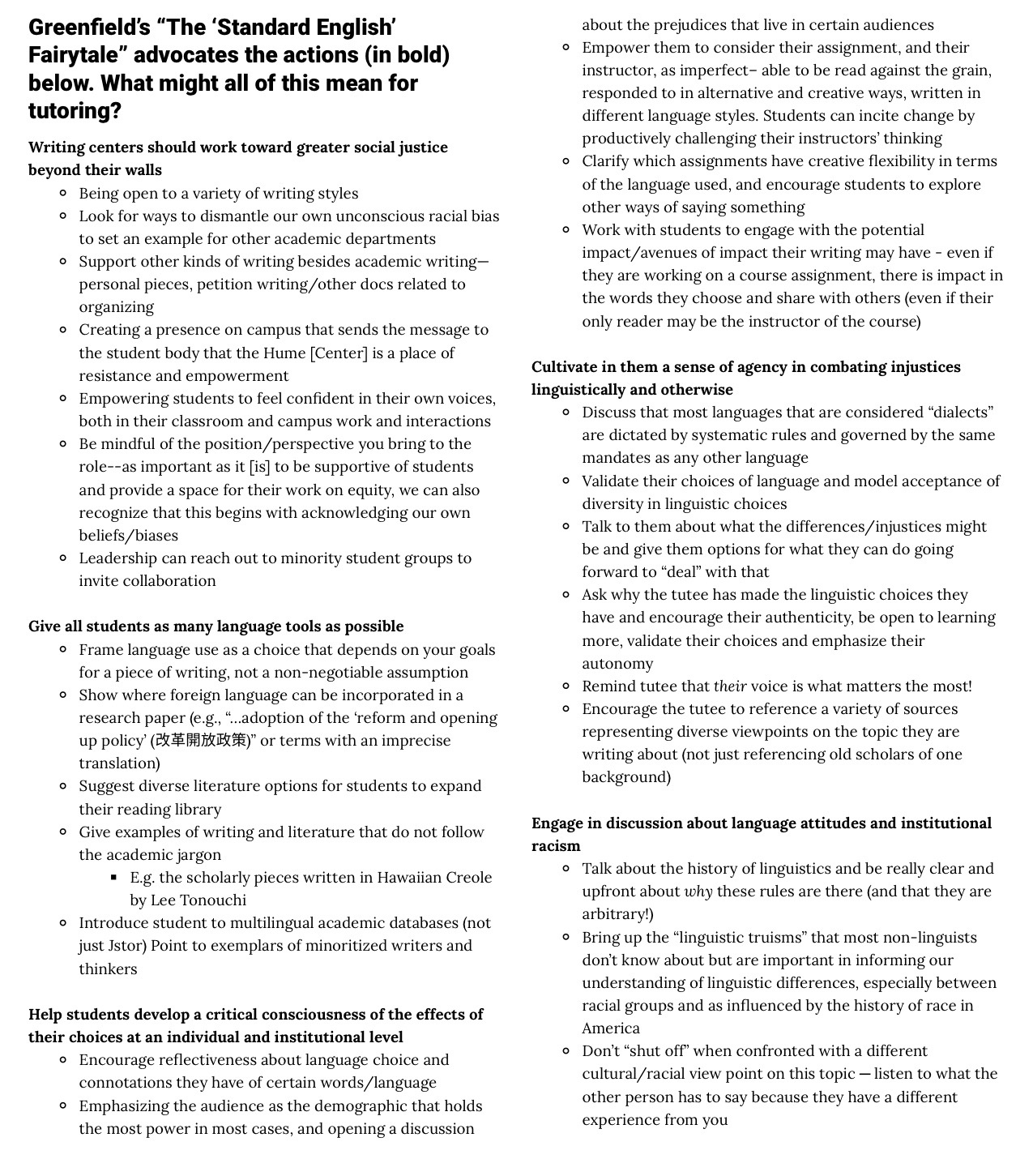

This work, cultivating tutors’ conscientization or growing critical awareness of writing tutoring as a site of resistance, is a gradual process not easily reducible to specific moments. Critical analysis of key texts, like Greenfield’s (2011) “The ‘Standard English’ Fairytale,” Garcia’s (2017) “Unmaking Gringo Centers,” Denny’s (2005) “Queering the Center,” Johnson’s (2011) “Racial Literacy and the Writing Center,” Blazer’s (2015) “21st Century Writing Center Staff Education,” Hall’s (2017) “Blogging as a Tool for Dialogic Reflection,” Micciche’s (2004) “Making a Case for Rhetorical Grammar,” and Talking Black in America, a documentary by the Language and Life Project, lays the groundwork for a recursive process of critical reading and engagement that develops students’ understanding of antiracist, racially just writing tutoring praxis.

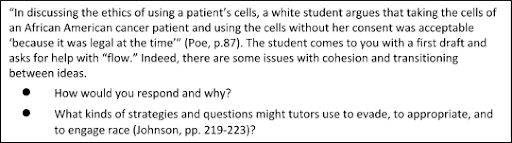

For example, after the tutors-in-training read Johnson (2011), they consider this scenario based on a Health Policy class that Mya Poe (2017) describes in “Reframing Race in Teaching Writing Across the Curriculum.”

Applying principles in the reading to a tutoring scenario enables tutors to grapple with the risks and rewards of engaging race directly during a tutorial. What might evasion, appropriation and engagement of race look like in this scenario? What happens if writers assert an ethically flawed position with which tutors disagree? Do tutors have a moral obligation to help writers recognize and unpack problematic viewpoints dealing with race, or is it okay to avoid such potentially uncomfortable encounters? The womanist ethic guiding my praxis makes such explorations central to tutor training.

Another example of tutors moving from reading and reflection to application occurs in response to Greenfield (2011). During an in-class activity, tutors type responses to the prompt below into a shared Google Doc.

These responses do not just arise from reading Greenfield; they emerge from a recursive process of reading, reflecting, and engaging that help tutors begin to think about their role as intervening in systems of oppression. Weekly reading reflections provide a space for grappling with ideas that are new to many, and small group discussions, tutoring observations, practice tutoring, and discussion of writing samples all allow tutors to delve deeper into the implications of our readings for anti-racist tutoring practice.

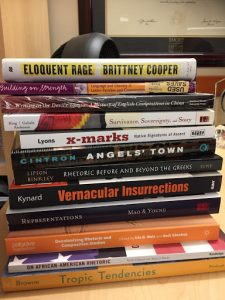

Of course, the work does not stop with the tutor training seminar. Once tutors begin collaborating regularly with writers, they participate in bi-quarterly professional development meetings that allow them to continue developing racial literacy and racially just writing tutoring praxis. One of these professional development activities involves excerpts from the cultural rhetorics materials in the Center’s library. Discussion of these texts (pictured here) enriches tutors’ knowledge of the rhetorical traditions of people of color and their appreciation for a more expansive range of literacies. We can then discuss the ways that this knowledge can inform tutoring practices.

Movement 3: Rejoicing

Weeping may linger for the night,

but joy comes with the morning

—Psalm 30:5b (NRSV)

Those who go out weeping,

bearing the seed for sowing,

shall come home with shouts of joy,

carrying their sheaves.

—Psalm 126:6 (NRSV)

An antiracist, racially just writing center culture extends beyond the individual tutorial. When writers and tutors enter the space, to the extent possible the environment should reflect the Center’s values. Centers favoring collaboration often position tables and chairs so that writers and tutors can sit side-by-side. They also choose décor intended to promote a welcoming atmosphere. What might Centers that value racial justice do to make visible their radical, unapologetic commitment to antiracism and racial justice? The Hume Center has put its commitments on display through a showcase of student artwork. In 2017, in alignment with the university writing program’s engagement of cultural rhetorics, the Hume Center focused its annual call for student artwork on the language and traditions of students of color:

In celebration of the rich cultural diversity at Stanford, the Hume Center for Writing and Speaking is curating an exhibit of student artwork that honors the languages and traditions of people of color throughout the diaspora. If you identify as a person of color and enjoy representing your tradition’s conception of self, community, or home, please consider being a part of our show. Your art will be displayed in our busy gallery, and we will recognize all participating artists at a show opening.

Art must be 2D; all mediums are accepted (oil, acrylic, watercolor, photography, drawings, etc.). Students may submit up to three pieces. Some funding may be available to support framing of your work. Art that is not selected for the show will be returned to its owner.

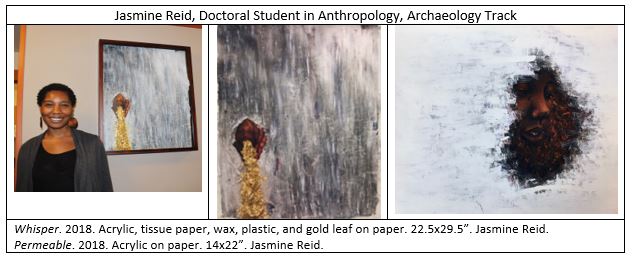

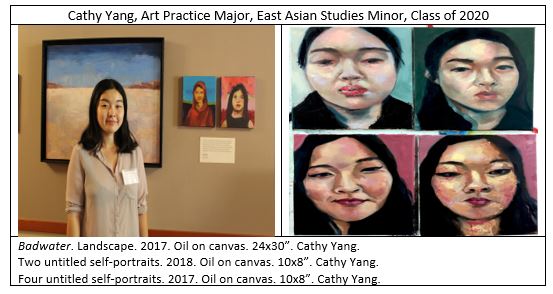

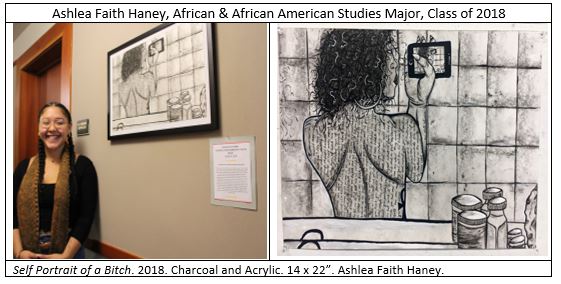

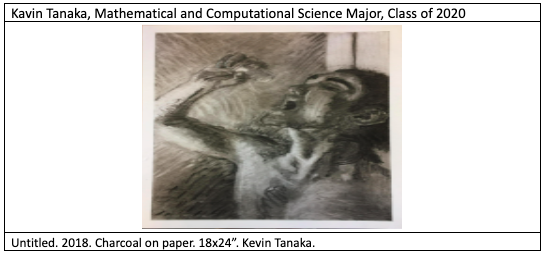

The previous year, the Art at Hume exhibit featured student work from a three-week Stanford Arts Intensive called “Painting Engaging Stories.” The showcase, part of the Center’s ongoing efforts to celebrate the range of communication arts, largely featured watercolor self-portraits. The 2018 and 2019 cultural rhetorics showcases displayed artwork in a greater variety of mediums and with a particular focus on diasporic representations of race and identity. The examples shared below with permission from the artists are mostly from the 2018 showcase, “Living Memory: A Cultural Awakening.” I see in these pieces the womanist spirit described earlier; the artwork resists marginalization, inviting viewers to look deeply at the lived experiences of these artists of color and to engage their racialized and gendered embodiment.

Jasmine Reid’s artwork “seek[s] to capture in appearance and in sentiment the feeling of peeling back the thick weight of stereotypes in order to breathe, to speak, and to be seen.” Having struggled with identity as a young Black girl in Boston, the doctoral student’s artwork juxtaposes “visibility and invisibility,” “recognition and misrecognition” to convey the diasporic experience.

Cathy Yang uses “variances in light, color, shape, and angle [to] contextualize the complexities of [her] personality…,” noting that we all have “seen” and “unseen” qualities that “make us who we are.”

Ashlea Faith Haney’s self-portrait is a rendering of a photograph of her reflection with additional elements, like the poem written on her back, that depict her self-perception as she was taking the photo. In this piece, as with her Honors thesis work, she “focused on exploring and uncovering the specific and sacred space the word ‘Bitch’ holds in the memories, identity, and languages of young Black womxn and femme.”

Kevin Tanaka’s[3] self-portrait captures a commonplace experience in their life at Stanford—taking medicine for mental illness. “As a member of the Japanese diaspora,” Kevin writes, “I am connected to a society whose taboo on mental illness does extraordinary harm.” Kevin hopes their artwork will encourage viewers to examine how they contribute to the obfuscation or illumination of mental illness.

The cultural rhetorics art displays have become a point of joy for the Center in its pursuit of antiracism and racial justice. Watching students view the artwork and read the artist statements before or after a tutorial reminds me of the ways that art contributes to cultural identity and to cultural life. These exhibits are one way, beyond the tutorial, that we are planting seeds of racial literacy and creating space for the marginalized to be seen and heard.

In Invitation

they came because of the wailing

the wailing of so many voices

who had a strong song

but who were choking from the lack of air

they came because of the weeping

the weeping of so many tears

that came so freely

on hot but determined faces

they came because of the hoping

the hoping of the beating heart

the fighting spirit

the mother wit tongues

the dancing mind

the world in their eyes

they came because they had no choice

to form a we

that is many women strong

and growing

—emilie townes, “they came because of the wailing” (2006)

A fifth womanist tenet, appropriation and reciprocity, speaks to questions often raised in response to epistemologies originating in Black experience: is it universally applicable, and do you have to be Black to do this work? You do not have to be a Black woman and/or working in any particular locale “to participate in solidarity with and on behalf of Black women who have made available, shared, and translated their wisdom, strategies, and methods for the universal task of liberating the oppressed and speaking truth to power” (Floyd-Thomas, 2006a, p. 250). Given the demographics of writing program leadership, I hope that this is welcome news. The few people of color leading writing centers and programs cannot do this work alone. We need partners within and across institutions who take antiracism and liberation seriously and are therefore willing to do the critical work of advocating for increased diversity among tutoring staff (and center administrators) as well as replacing oppressive practices with life-giving ones. There are no one-size-fits-all approaches that will be optimal in every context, but you can take the womanist ethic that I have presented and consider ways of applying it in your context.

Radical subjectivity: How can I develop a mature self-awareness of racism in my institutional context and leverage my authority toward subverting it?

Traditional communalism: How can I counter false narratives of Black inferiority and deficiency at work in my institutional context?

Redemptive self-love: How can I support Black women and other marginalized peoples in rejecting dehumanizing stereotypes and reclaiming their truer personhood?

Critical engagement: How can I use my position to seek the greatest degree of freedom and justice for the oppressed, recognizing the ways in which oppression can be interlocking?

Whether your center is large or small, offers a full tutor training course or independent training materials, I encourage you to find a place to begin. How might you centralize racial justice in your tutor training curriculum rather that attaching it to the end like an addendum? What interactive video modules could you create in lieu of or in addition to a tutor training course? What opportunities for tutor-to-tutor and tutor-to-writer dialogue could you arrange during the academic year to promote antiracism and racial justice? Creating a world in which we all can flourish demands our intentional and relentless investment.

Notes

- Excerpts from tutoring philosophies submitted in the spring 2020 tutor training seminar are presented here with the students’ permission. ↑

- “Diversity” and “diverse,” in my usage, refer to all categories of marginalization, including race, gender, class, sexual orientation, and ability. ↑

- Kevin Tanaka is a pseudonym chosen by the student artist. ↑

References

Bauman, D. (2018, November 14). Hate crimes on campuses are rising new FBI data show. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Bawarshi, A. and Pelkowski, S. (1999). Postcolonialism and the idea of a writing center. The Writing Center Journal (19)2, 41-58.

Blazer, S. (2015). Twenty-first century writing center staff education: Teaching and learning toward inclusive and productive everyday practice. The Writing Center Journal, (35)1, 17-55.

Bowen, E. (2018, February 12). Kimball posters ignite free speech. The Stanford Daily.

Brooks, J. (1991). Minimalist tutoring: Making the student do all the work. Writing Lab Newsletter (15)6.

Camarillo, E. (2019). Dismantling neutrality: Cultivating antiracist writing center ecologies. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, (16)2, 1-6.

Cannon, K. G. (1985). The emergence of black feminist consciousness. In L. M. Russell (Ed.), Feminist interpretation of the Bible (pp. 30-40). Westminster John Knox Press.

Cannon, K. G. (1988). Black womanist ethics. Scholars Press.

Cannon, K. G. (1997). Womanism and the soul of the Black community. Continuum.

Corbett, S. J. (2008). Tutoring style, tutoring ethics: The continuing relevance of the directive/nondirective instructional debate. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, (5)2.

Starkman, R. (2020, July 24). Dropping the N-Word in College Classrooms. Inside Higher Ed.

Denny, H. (2005). Queering the center. The Writing Center Journal, (25)2, 39-63.

Diab, R., Ferrel, T., Godbee, B., & Simpkins, N. (2013). Making commitments to racial justice actionable. Across the Disciplines (10). https://wac.colostate.edu /docs/atd/race/diabetal.pdf

Floyd-Thomas, S. M. (Ed.) (2006a). Deeper shades of purple: Womanism in religion and society. New York University Press.

Floyd-Thomas, S. M. (2006b). Mining the motherlode: Methods in womanist ethics. The Pilgrim Press.

García de Müeller, G. and Ruiz, I. (2017). Race, silence, and writing program administration: A qualitative study of US college writing programs. WPA: Writing Program Administration, (40)2, 19-39.

García, R. (2017). Unmaking gringo-centers. The Writing Center Journal, (36)1, 29-60.

Geller, A. E., Eodice, M., Condon, F., Carroll, M., & Boquet, E. H. (2007). The everyday writing center: A community of practice. Utah State University Press.

Greenfield, L. (2011). The ‘Standard English’ fairy tale: A rhetorical analysis of racist pedagogies and commonplace assumptions about language diversity. In L. Greenfield and K. Rowan (Eds.), Writing centers and the new racism: A call for sustainable dialogue and change (pp. 33-60). Utah State University Press.

Grimm, N. (2011). Retheorizing writing center work to transform a system of advantage based on race. In Greenfield, L. and Rowan, K. (Eds.), Writing centers and the new racism: A call for sustainable dialogue and change (pp. 75-99). Utah State University Press.

Hall, R. M. (2017). Blogging as a tool for dialogic reflection. In Around the texts of writing center work: An inquiry-based approach to tutor education (pp. 105-124). University Press of Colorado and Utah State University Press.

Hutcheson, N., Cullinan, D. (Directors). (2018). Talking Black in America [Documentary]. The Language & Life Project at NC State.

Johnson, M. T. (2011). Racial literacy and the writing center. In L. Greenfield and K. Rowan (Eds.), Writing centers and the new racism: A call for sustainable dialogue and change (pp. 222-238). Utah State University Press.

Johnson, K. (2017). The womanist preacher: Proclaiming womanist rhetoric from the pulpit. Lexington Books.

Jordan, Z. (2019). Clarity and creativity as womanist ethics for teaching and evaluating theological writing. Teaching Theology & Religion, (22), 253-268.

Kerr, E. (2018, February 1). White supremacists are targeting college campuses like never before. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Lemons, G. (Ed.) (2019). Building womanist coalitions: Writing and teaching in the spirit of love. University of Illinois Press.

Lockett, A. (2018). A touching place: Womanist approaches to the center. In Denny, H., Mundy, R., Naydan, L. M., Sévère, R., and Sicari, A. (Eds.), Out in the center: Public controversies and private struggles (pp. 28-42). Utah State University Press.

Lockett, A. (2019). Why I call it the academic ghetto: A critical examination of race, place, and writing centers. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, (16)2, 20-33.

Lunsford, A. (1991). Collaboration, control, and the idea of a writing center. The Writing Center Journal, (12)1, 3-10.

Mackiewicz, J., and Thompson, I. (2014). Instruction, cognitive scaffolding, and motivational scaffolding in writing center tutoring. Composition Studies, (42)1, 54-78.

Marshall Turman, E. (February, 2019). Black women’s faith, black women’s flourishing: Womanist theology proclaims a future beyond the strongholds of racism, sexism, and injustice. The Christian Century.

McCrary, D. (2001a). Speaking in tongues: Using womanist sermons as intra-cultural rhetoric in the writing classroom. Journal of Basic Writing, (20)2, 53-70.

McCrary, D. (2001b). Womanist theology and its efficacy for the writing classroom. College Composition and Communication, (52)4, 521-552.

Micciche, L. R. (2004). Making a case for rhetorical grammar. College Composition and Communication, (55)4, 716-737.

Myers, S. A. (2003). Reassessing the “proofreading trap”: ESL tutoring and writing instruction. The Writing Center Journal, (24)1, 51-70.

Poe, M. (2017). Reframing race in teaching writing across the curriculum. In Condon, F. and Young, V. A. (Eds.), Performing antiracist pedagogy in writing, rhetoric and communication (pp. 87-105). University Press of Colorado.

Pfeiffer, T. (2018, February 20). ‘Racism lives here’: What’s happening at Stanford Law. Stanford Politics.

Phillips, L. (Ed.) (2006). The womanist reader. Routledge.

Riggs, M. (2011). Living as religious ethical mediators: A vocation for people of faith in the twenty-first century, In K. G. Cannon et al. (Eds.) Womanist Theological Ethics: A Reader, pp. 247-253), Westminster John Knox Press.

Shalby, C. (2019, July 18). Stanford investigating after noose hanging from tree is found on campus. Los Angeles Times.

Swales, J. (2011). The concept of discourse community. In Downes, D. P., and Wardle, E. (Eds.), Writing about writing: A college reader. Bedford St. Martin’s. (Original work published 1990)

townes, e. (2006). they came because of the wailing. In Floyd-Thomas, S. M. (Ed.), Deeper shades of purple: Womanism in religion and society (p. 251). New York University Press.

Walker, A. (1983). In search of our mother’s gardens: Womanist prose. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.